The Battle of Gonzales

The Texans learned that General Cos was leading a large military force into the state. The Mexican government said that the troops were being sent to protect the settlements from the Indians. The Texans didn't believe this story. They didn't feel that they needed protection. They were sure that the real purpose of the troops was to force them to accept the government in which Santa Anna was dictator. Also, several citizens of Anahuac were arrested by the Mexican tax officials. Brother William Barret Travis gathered 25 men and freed the prisoners. They made the Mexican tax officials promise to leave Texas.

A call went out for a meeting of the Texans in order that they might discuss these problems. The meeting was to be known as the Consultation. A quarrel immediately developed over the wisdom of holding such a meeting. At this time there were two political parties in Texas. One was known as the war party, and the other as the peace party. The war party, which favored the meeting of the Consultation, was ready for an immediate declaration of independence. The peace party opposed the meeting. This party believed that revolution was bound to come, but that the Texans should delay it as long as possible. The members of the peace party argued that the longer the revolution was delayed the stronger Texas would be and the better her chances of winning independence. Austin returned from Mexico while this dispute was in progress, and both sides turned to him for advice in the matter.

Many Texans hoped that the Consultation might be able to find some solution to the problem, but fighting began before the date on which it was to meet. The fact that fighting was in progress delayed the meeting of the Consultation. The first clash between Texan and Mexican troops took place at Gonzales on October 2, 1835.

Gonzales is most famous as the "Lexington of Texas" because it was the site of the first skirmish of the Texas Revolution. This term is an allusion to the Battle of Lexington, the first battle of the American Revolution. In 1831, the Mexican government gave the settlers a small cannon (believed to actually have been a swivel gun) for protection against Indian attacks.

The Battle of Gonzales started with a dispute over the cannon which the people of the town had had in their possession for four years. The cannon had been obtained for use in case of Indian attacks. The Mexican commander at San Antonio, Colonel Ugartechea, decided that the gun was no longer needed and asked that it be given up. A corporal and four men were sent to take: possession of the cannon and deliver it to San Antonio. The people of Gonzales, thinking that they might have need for the gun, refused to give it up.

Messengers were sent to neighboring towns asking for volunteers to help defend the cannon. Ugartechea sent Lieutenant Castaneda (kas'tan-ya'da) with about 100 men to take the gun. When the Mexican force reached Gonzales, it found about 160 Texans, commanded by Colonel John H. Moore :and Lieutenant Colonel J. W. E. Wallace, ready to defend the cannon. The gun was first buried in a peach orchard but was later mounted on an oxcart for use against the Mexicans.

The Mexican force was attacked by the Texans on the morning of October 2, 1835. The cannon, which had been loaded with iron balls and pieces of chain, was used in the battle. It made considerable noise but did little damage. Tradition says that the cannon was decorated with a large flag bearing the challenge: "Come and Take It.." The fighting lasted only a few minutes. The Mexicans, outnumbered and perhaps frightened by the cannon, fled. They left one of their number dead upon the field. No Texan was killed.

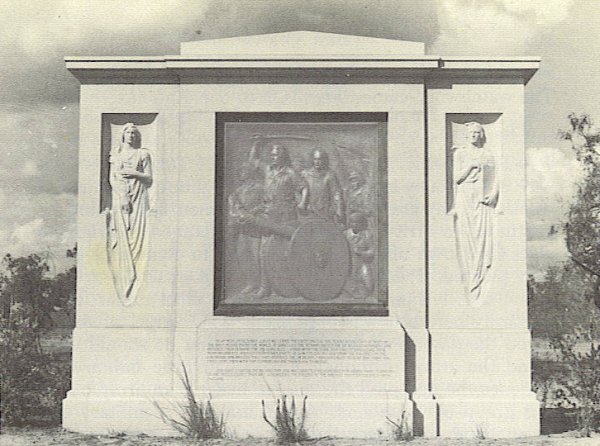

The Monument At Gonzales

On October 9, just one week after the Battle of Gonzales, General Cos reached San Antonio with an army of more than a thousand men. The Texans had openly challenged Mexican authority. They knew, and General Cos knew also, that war had begun.

No © Copyright.

|

Page Crafted By Corky

The Pine Island Webwright